60-plus years of music history and good fortune

April 5th, 2002

![]() The world has changed a great deal since 1938. That was the year fiddle and mandolin player Johnny Gimble, at age 13, first appeared with his brothers on radio station KGBK in their hometown of Tyler, Texas. In the intervening decades, Gimble has lived one of the most remarkable careers in modern music. Although he’s best known as a former member of Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys, the 75-year-old Gimble has played and recorded with some of the most important musical figures of the 20th century.

The world has changed a great deal since 1938. That was the year fiddle and mandolin player Johnny Gimble, at age 13, first appeared with his brothers on radio station KGBK in their hometown of Tyler, Texas. In the intervening decades, Gimble has lived one of the most remarkable careers in modern music. Although he’s best known as a former member of Bob Wills’ Texas Playboys, the 75-year-old Gimble has played and recorded with some of the most important musical figures of the 20th century.

According to Texas Folklife Resources, then, the time has come to pay tribute to the man they call the “King of Swing Fiddle.” Austin’s nonprofit preservationists of all things Lone Star and rootsy, TFR is honoring Gimble this Saturday with an all-star bash titled “Under the X in Texas: A Tribute to Johnny Gimble” at the Paramount Theatre. Hosted by Asleep at the Wheel’s Ray Benson, the evening’s musical lineup includes just a few of the artists from Gimble’s past, including Guy Clark, Tracy Nelson, Connie Smith, the Hot Club of Cowtown, and Floyd Tillman. Benson, for his part, can’t say enough good things about Gimble.

According to Texas Folklife Resources, then, the time has come to pay tribute to the man they call the “King of Swing Fiddle.” Austin’s nonprofit preservationists of all things Lone Star and rootsy, TFR is honoring Gimble this Saturday with an all-star bash titled “Under the X in Texas: A Tribute to Johnny Gimble” at the Paramount Theatre. Hosted by Asleep at the Wheel’s Ray Benson, the evening’s musical lineup includes just a few of the artists from Gimble’s past, including Guy Clark, Tracy Nelson, Connie Smith, the Hot Club of Cowtown, and Floyd Tillman. Benson, for his part, can’t say enough good things about Gimble.

“He’s been like a second father to me,” declares Benson. “Although he’s never officially been in the band, he’s played with Asleep at the Wheel hundreds of times and played on probably 80% of our records. Johnny is one of the most original improvisers in the world, period. I would put him up there with any of the greatest soloists in jazz, because he’s totally original, technically superior, and full of incredible ideas that just flow out of him.”

Notice that Benson said jazz and not country. Western swing, which both Gimble and Asleep at the Wheel have kept alive over the years, is considered a form of country music, but both men declare that, “Western swing is Dixieland on strings.” Or as Gimble is fond of saying, “I’ve always liked the stuff that kicks.” Also kicking is the very act of conversing with “The king of swing fiddle,” which is like walking through a history book.

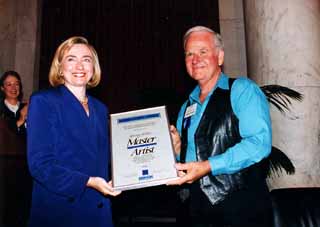

He greets me in the driveway of his modest Dripping Springs home with a smile and a warm handshake, and invites me into his den. A violin and a mandolin are set up; both plugged into a small amp. A Grammy Award sits on top of some stereo equipment. There are lots of pictures on the walls, photographs of folks he’s played with over the years, including a few of the Texas Playboys and one of Hillary Clinton presenting Gimble with the National Heritage Fellowship Award from the NEA.

I ask about the fiddles — there’s another on the table nearby — and he explains that both are over 200 years old. He picks up the one near the amp and plucks a few strings, relating the tale of how he found it. Gimble says it’s his now famous five-string fiddle, converted for a bigger sound from four strings, which it had in Germany during World War II when less was regulation.

The instrument on the table he describes as a gift from a friend who trades instruments. It has Bob Wills’ name engraved on it in letters so tiny you need a magnifying glass to read them. Whether it actually belonged to Wills can’t be proved, admits its owner, though he’s reasonably sure his onetime employer played a model that was very similar at some point. Gimble’s wife Barbara checks in on us once in awhile, but otherwise, we talk about the opportunities life has presented him.

“When I get asked for advice for a young person starting in the music business, I tell them, ‘Play every chance you get and be real lucky,’” he says with a smile.

Ballyhooing Brotherhood

Born in the East Texas town of Tyler on May 30, 1926, Gimble and his four brothers grew up on a 100-acre farm six miles east of there. He says it was his older brother Jack who was the first of the boys to pick up an instrument. Eventually, they all began to play, with Bill, who had started on the fiddle and mandolin, sharing what he had learned with Johnny, who was 9 at the time.

Rex Allen’s Men of the West

Mad Hatters: Johnny Gimble (r) with

Rex Allen’s Men of the West, circa 1963-64

“We played a few gigs in ’38,” he recalls. “There was a milling company, Marsen Milling in Sherman, Texas, that had a sales representative, a big old guy who weighed about 300 pounds by the name of Big Boy Green. He’d go out on Saturday and advertise Peacemaker Flour, calling the band the Peacemaker Boys. He would come by and pick up us — Jack, Bill, Gene, and I — and we’d drive down in East Texas, get up on a truck in front of a grocery store, and ballyhoo Peacemaker flour.

“That was our first paying gig. We worked for him a summer or two. He’d come by at 5am; he had an old 1936 Ford with the horn speakers on it and an amplifier that had a turntable. He would pull up in front of the store with an extension cord and start playing records. When a crowd gathered, we’d get up and go to playing for him. We would get home 10-11pm. He paid us $2 apiece.

“That was real good, and that was when I got spoiled. Because I was never very good at picking cotton, and then I only made fifty cents or $1 a day. People would work for $1 a day during the Depression. So we would get $2 for playing music and just having fun. I think that as a result of that it was not just the money, but we enjoyed doing it. All of us wanted to play and we wanted to have a band.”

Not long after, the Gimble brothers began playing a regular radio show on KGKB in Tyler — three days a week for 15 minutes at a time. Following high school, Johnny jumped ship to play with the Shelton brothers, who had a group called the Sunshine Boys that was on the radio in Dallas and Shreveport. It was 1943. When the war intervened, Johnny joined the Army. Upon returning from Europe, he worked with a variety of radio show and dancehall bands, most notably with guitarist Jesse James, who was on the air at KTBC, the biggest station in Austin.

“In those days,” explains Gimble, “if you could get a band together, you could get a radio station to give you some time, 15 or 30 minutes, and you would play for nothing, but you could advertise your dates. Then, you would play as far as the signal would go. So we played as far as Corpus Christi, Bryan, and Brownwood.”

Playing for the Yankees

Gimble’s first big break came in 1949 when he was in a band called the Rhythmaires that was playing in Corpus Christi. They were the opening act for Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys.

“I was onstage playing the mandolin,” recalls Gimble, “and Tiny Moore [Wills’ mandolin player] came in, heard me playing, and yells, ‘I’m gonna kill you.’ When we took a break, Tiny said Jesse [Ashlock, Wills’ fiddle player] was gonna leave, and ‘Would you be interested in playing with the Wills band?’ It was like being a baseball player and someone asking if you wanted to play for the New York Yankees.

“His was the No. 1 band. They were playing at Dessau Hall up in Austin not long after that, and they asked me to come up and sit in with them there, and I did. Afterwards, [rhythm guitarist] Eldon Shamblin said, ‘You got it if you want it. Turn in your notice and come join us in a couple of weeks.’ So I packed up the car and met them in Oklahoma.”

“His was the No. 1 band. They were playing at Dessau Hall up in Austin not long after that, and they asked me to come up and sit in with them there, and I did. Afterwards, [rhythm guitarist] Eldon Shamblin said, ‘You got it if you want it. Turn in your notice and come join us in a couple of weeks.’ So I packed up the car and met them in Oklahoma.”

During this period, Wills and his band were going through a tumultuous time. Western swing had lost a great deal of its popularity, and most dancehalls were less than full. Wills was battling the bottle, which led him to miss shows. He was also changing his home base from Sacramento to Oklahoma City to Dallas.

Meanwhile, there was constant turnover in the legendary group. Gimble relates how band members had to sit with Wills during the day when they were on the road to make sure their employer didn’t drink and was thus able to perform that night. Gimble recalls one day in particular when he poured a fifth of whiskey down the sink in front of Wills, something he claims Wills never forgot.

Gimble played with the Playboys for most of the Fifties and is rightfully proud of that period in his career. To be sure, aside from the band’s namesake, Gimble is the most famous Wills sideman from that time. During that same decade, while in Dallas, Gimble also became part of the Big D Jamboree band. Through this association, he managed to connect with record producer Don Law, who used the fiddle player on sessions with Lefty Frizzell, Marty Robbins, and Ray Price.

In the latter part of the decade, Gimble even hosted a television show in Waco, Johnny Gimble & the Homefolks, on KWTX-TV for three years. It was in Waco that the fiddle player first met a young musician by the name of Willie Nelson.

“We needed a bass player, because our regular man was out of town,” remembers Gimble. “Willie filled in — he needed the work. He had a young family to feed. From then on, anytime he could use me, he would have me play with him.”

Million Dollar Bow

In 1961, Gimble was fiddler for Five Star Jubilee, a show broadcast on NBC from Springfield, Mo. It was there that he met famed cowboy singer Rex Allen, the two working together for a time at rodeos and other gigs. Following a brief layoff from the music business in the mid-Sixties, Gimble then moved to Nashville and became the most in-demand fiddle player in Music City from 1968-78.

“Ernest Tubb’s bass player was Jack Drake,” explains Gimble. “He had been trying to get me to play with Tubb, and one day I sat in with them. Ernest thought I was auditioning, but I thought I was just visiting. While we were playing Jack said, ‘Gimble, you call a tune.’ I said, ‘Everybody dances to “Faded Love,”‘ and I kicked it off and sang, and at the end, the audience cheered. Old Tubb was sitting backstage and hollered, ‘Tell him he’s hired.’

“After I told Jack I wasn’t interested in playing with a traveling band — that I wanted to move to Nashville to do studio work — he told me about his brother Pete, who had a publishing company and was partners in a record label, Stop Records. He said if I moved up there that Pete would use me on some weekend gigs and book me on all the Stop Record sessions and try to get me work around town.

“So we sold our house in Waco, moved up there, and I started to work for Pete. I’d do free demo sessions for him. He told me the kiss of death is to go in and ask for work in Nashville. I don’t know how much truth there is to that. I just made my presence known.”

He most certainly did. During the next 10 years, Gimble recorded with Asleep at the Wheel, Chet Atkins, Joan Baez, Jimmy Buffett, Guy Clark, Jessi Colter, the Everly Brothers, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Loretta Lynn, Paul McCartney & Wings, Reba McEntire, Tracy Nelson & Mother Earth, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Pure Prairie League, Leon Russell, Connie Smith, Conway Twitty, Porter Wagoner, and too many others to list.

In 1975, and four consecutive years after that, Gimble was named the Country Music Association’s Instrumentalist of the Year. He was feted as Fiddler of the Year nine times by the Academy of Country Music. During this period, Gimble was also a member of Hee Haw’s Million Dollar Band, featuring the best players in Nashville, including Chet Atkins, Boots Randolph, Floyd Cramer, Bob Moore, Pig Robbins, Harold Bradley, and Grady Martin.

One of the most memorable moments of his stint in Nashville occurred during a session with the inimitable country diva Connie Smith. Gimble had played a particularly poignant fiddle solo on Smith’s “If It Ain’t Love,” which touched the singer so much that she had a handwritten note copied and mailed out with all deejay copies of the album to alert them to the fact that Gimble was the player responsible.

“I wanted it to be released as a duet,” claims Smith today, “but the record company refused, so that was the next best thing. Johnny played on most of my records over the years. He’s as steady as a rock and a wonderful gentleman.”

Given his overwhelming success in Nashville, the question that’s begged is why did Gimble decide to leave?

“Texas was home,” he says plainly. “We went to Anchorage to get rich in 1959. Someone told us, if you drive a nail, you could make $100 a day in construction work. We were hungry and we stayed there for a year and a half. But I never did plan to stay there, the same with Nashville. I was gonna go up there and work, but Texas was home. I used to tell people, ‘I wasn’t gonna die and go to Texas, I was gonna go to Texas and die.’”

Every Chance He Gets

In the 30-plus years since then, Gimble has remained active. He does session work in Texas and commutes occasionally to Nashville. He can be heard on eight of George Strait’s albums and has also worked with local country artists such as Libbi Bosworth, Jesse Dayton, Kimmie Rhodes, Toni Price, the Texas Tornadoes, Don Walser and a whole passel more. He’s won two Grammys with Asleep at the Wheel.

Gimble has appeared on Austin City Limits more than any other individual and makes regular appearances on Prairie Home Companion. One of his more impressive undertakings is a weeklong summer music camp held in July in Taos, N.M., called Swing Week, where he and members of his band tutor young musicians in fiddle, bass, and guitar.

In 1999, Gimble had a stroke, but it’s hardly slowed him down. He still performs as much as he’s able to. He appeared at the most recent Austin Music Awards show, and along with he and his son Dick, has a band called Texas Swing that just released a lively compact disc titled Just for Fun. As to whether the stroke affected his motor skills, the playing, he admits that things are a bit tougher these days.

“It’s work now,” he says candidly. “It’s different. It’s strange. Other players say, ‘Now you know how the rest of us feel.’”

Looking at my watch, I realize we’ve talked almost four hours. Gimble could tell stories about his life for days on end and it would never cease to be fascinating. The sun is going down on the glorious view of the Texas Hill Country out his den window. It’s probably time for me to go. I mention that he should gather up these stories and write an autobiography. No one has seen the past 60 years from his perspective, and it’s a story that deserves not only to be told, but honored for the passion and simple humanity of the man who lived it.

“Chet Atkins always told me, ‘You oughta write a book,’” reveals Gimble, “but … .”

His voice trails off, like it’s too much to bear at the moment. I thank him for his time and drive off into the hills, recalling something Gimble said early in our conversation: “Play every time you get a chance, and be real lucky.” How lucky for us that Johnny Gimble is around in our lifetime and still playing every chance he gets.

Copyright © 1995-2002 Austin Chronicle Corp. All rights reserved.